Abstract

Boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) have attracted attention for their predicted extraordinary properties; yet, challenges in synthesis and processing have stifled progress on macroscopic materials. Recent advances have led to the production of highly pure BNNTs. Here we report that neat BNNTs dissolve in chlorosulfonic acid (CSA) and form birefringent liquid crystal domains at concentrations above 170 ppmw. These tactoidal domains merge into millimeter-sized regions upon light sonication in capillaries. Cryogenic electron microscopy directly shows nematic alignment of BNNTs in solution. BNNT liquid crystals can be processed into aligned films and extruded into neat BNNT fibers. This study of nematic liquid crystals of BNNTs demonstrates their ability to form macroscopic materials to be used in high-performance applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) are high aspect ratio rod-like nanostructures a few nanometers in diameter and microns long1. Chemically, BNNTs are composed of alternating boron and nitrogen atoms in a hexagonally-bonded sheet, scrolled to form a seamless cylindrical structure that gives rise to several unique properties2. In addition to being mechanically strong3,4, BNNTs are thermally conductive5, electrically insulating2, neutron-shielding6, piezoelectric7, and thermally stable up to 900 °C in air8,9. These properties are desirable for many applications, including aerospace, electronics, and energy-efficient materials. However, the utility of BNNTs is not yet fully realized, because their remarkable properties have only been observed at the microscopic level10. Future improvements in material quality and processing techniques will enable high-performance neat BNNT articles with extraordinary properties for use in extreme environments.

The inherent properties of nanoscale building blocks can be translated to the macroscopic scale by controlling long-range ordering, as has been achieved with carbon nanotubes (CNTs)11, structural analogs of BNNTs that share many of their desirable properties, apart from superior thermal stability12. For example, closely packed and highly aligned CNT fibers yield high performance (e.g., tensile strength13 above 4 GPa and electrical conductivity13 above 10 MS/m) via multiple routes, including direct spinning14,15, wet spinning16,17,18, and carpet spinning19,20. Thus far, none of these methods has been effectively employed to produce ordered BNNT materials. Of these routes, wet spinning appears most easily adapted to processing BNNTs because it is independent of synthesis method. Yet, wet spinning requires a solvent for the nanotubes and preferably the formation of a nanorod liquid crystal. Dispersions of individualized BNNTs can be achieved using chlorosulfonic acid (CSA)21. Kleinerman et al. hypothesized that protonation of nitrogen atoms of the outer BNNT wall confers a net positive charge to their surface; positively charged BNNTs repel each other leading to their individualization, as is the case for CNTs21. However, the bond structure of BNNTs would localize protons on the nitrogen atoms—unlike in CNTs, where shared π electrons favor delocalization and hence further stabilization of positive charges when CNTs are dissolved in acids22. This less effective charge stabilization (and charge localization on the nitrogen atoms) is likely to lead to some residual long-range attraction of BNNTs in CSA (which is absent for CNTs in CSA23), consistent with the higher-than-predicted isotropic-nematic phase transitions observed in this work. Thus far, the formation of BNNT liquid crystals has not been attained, possibly because of sample impurities (e.g., hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) and elemental boron24), which hinder the individualization and alignment of BNNTs. Previous work has suggested spontaneous ordering of DNA-BNNT hybrid systems, but aligned structures were only observed in dried films of DNA-wrapped BNNTs after solvent removal by filtration25 or evaporation26.

Here, we show that high-quality, purified BNNTs dissolve in CSA to form liquid crystals, including bipolar nematic tactoids, at concentrations as low as 170 ppm; these domains can be merged into bulk nematic domains using mild sonication. We image the BNNT liquid crystalline structure via cryogenic electron microscopy. We show that BNNT liquid crystals can be processed into aligned films and fibers using existing scalable techniques.

Results and discussion

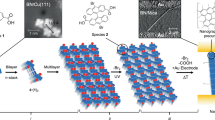

We synthesize the BNNTs via the high-temperature-pressure method (HTP)24 and purify them to remove residual elemental boron, producing “lightly processed” BNNTs (LP-BNNTs). LP-BNNTs are further purified to remove non-nanotube BN, producing “highly processed” BNNTs (HP-BNNTs)—see “Methods”. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of LP-BNNTs and HP-BNNTs in air (Supplementary Fig. 1) shows no mass gain from oxidation below 900 °C, indicating the absence of elemental boron impurities. The 35% mass increase at 1100 °C due to the oxidation of boron nitride is consistent with TGA from previous reports of pristine BNNTs27. Because TGA does not distinguish between the oxidation of BNNTs and other boron nitride allotropes, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are used to assess relative BNNT purities. Figure 1a, c shows that LP-BNNTs samples contain agglomerates of h-BN (white arrows) that envelop overlapping BNNT bundles to create an apparent crosslinked BNNT network. The HP-BNNT samples (Fig. 1b, d) have a lower concentration of smaller h-BN aggregates (white arrows). TEM shown in Fig. 1d reveals that the few remaining non-nanotube structures in HP-BNNTs are few-layer stacks of h-BN. Consistent with literature values28, the h-BN stack exhibits an interlayer spacing of 0.337 nm (Supplementary Fig. 2), determined by selected area fast Fourier transform.

a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of LP-BNNTs. b SEM of HP-BNNTs. c Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of LP-BNNTs on perforated carbon grid. d TEM of HP-BNNTs on perforated carbon grid with inset TEM image of residual contaminants in HP-BNNTs. A selected area fast Fourier transform of the inset image indicates an interlayer spacing of 0.337 nm, the same as for h-BN (Supplementary Fig. 4). Electron microscopy shows a reduction in non-nanotube structures upon more purification. Arrows indicate hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) contaminants in both LP-BNNTs and HP-BNNTs. e Photograph of solutions of (left) HP-BNNTs and (right) LP-BNNTs in chlorosulfonic acid (CSA) at 1700 ppmw in 4 mm path length quartz cuvettes placed in front of the Rice University shield. Scattering of the LP-BNNT solution occludes details in the design. f Cryogenic-TEM of 4000 ppmw HP-BNNTs in CSA showing amorphous material covering BNNTs (black arrow), and faceted structures (white arrow).

Purified BNNTs spontaneously dissolve in CSA upon high-shear mixing to form homogenous liquids. LP-BNNTs in CSA (Fig. 1e, right) appear white and opaque, likely from scattering of micron sized aggregates of h-BN and BNNTs (visible in Fig. 1a, c) that do not dissolve well. Conversely, HP-BNNT solutions (Fig. 1e, left) typically have a peach color and are more transparent to the eye at the same concentration due to reduced optical scattering from individualization, owing to a superior purity. UV–visible and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy indicate that dissolution in CSA does not chemically alter BNNTs (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Cryogenic-TEM (Cryo-TEM) of low-concentration HP-BNNT solutions (Fig. 1f) shows individualized BNNTs in CSA. Cryo-TEM also reveals that trace contaminants in HP-BNNTs (black and white arrows) envelop short segments of individual BNNTs. HP-BNNT diameter and length are characterized by AFM (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d), diameter and number of walls by TEM (Supplementary Fig. 5e–g), and aspect ratio via capillary thinning extensional rheometry29 (Supplementary Fig. 6). The results summarized in Table 1 show that all the techniques yield consistent results (within measurement error), with a typical aspect ratio of ~300 for HP-BNNT.

Polarized light microscopy (PLM) images of BNNT solutions in sealed capillaries reveal important information about the solution quality such as degree of dissolution and anisotropy. LP-BNNTs at 7000 ppm by weight (ppmw) (Fig. 2a) have a gel-like behavior and show little birefringence, indicating no molecular orientational ordering, likely because BNNTs are trapped in the h-BN-induced network visible in Fig. 1a, c. Conversely, solutions of HP-BNNTs (Fig. 2b) display a brightly birefringent Schlieren texture, a hallmark of nematic liquid crystals30. The presence of areas that remain dark for all crossed-polarizer angles (red arrows) suggests that the solution is biphasic (isotropic-nematic). Brief bath sonication of these filled capillaries promotes the merging of the nematic regions into larger domains that span the 1 mm width of the capillary (Fig. 2c). The unpolarized light image of HP-BNNTs (Fig. 2b, left panel) shows 20 μm long ellipsoidal regions dispersed throughout the sample. The white arrows in Fig. 2b point to the same ellipsoidal structure. At high magnifications (Fig. 2d), the ellipsoids display the birefringence pattern of bipolar tactoids, small spindle-shaped nonequilibrium nematic droplets surrounded by isotropic media that form in concentrated solutions of elongated particles31,32. While the tactoids in unsonicated capillaries are stable for over 1 year, the sonicated liquid crystalline domains are stable in sealed capillaries for at least 6 months, limited by CSA degradation due to the slow ingress of moisture from sealed capillary ends that can be damaged by sonication. Likely, sonication provides enough energy to overcome the kinetic barriers that prevent the merging of tactoids. Tactoids are observed in solutions of HP-BNNTs at all studied concentrations, from 50 ppmw to 7260 ppmw (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The isotropic cloud point for these BNNTs was determined to be 170 ppmw (220 ppm by volume). This determination was made using images of capillary-sonicated solutions in Supplementary Fig. 7c, d so that BNNTs in tactoids persisting after dilution would fully disperse. Interestingly, the isotropic cloud point for these BNNTs is an order of magnitude lower than what would be expected for CNTs of similar aspect ratio29. This is consistent with less effective charge stabilization relative to CNTs, resulting in residual attraction and lowered isotropic cloud points, as observed in CNT solutions with decreasing acid strength23,33. Nematic domains of HP-BNNTs (8000 ppmw = 0.8 wt%) are directly visualized in Fig. 2e by cryogenic scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM), which shows an aligned domain surrounded by isotropic BNNTs, consistent with the non-birefringent areas present in Fig. 2b. No tactoids were observed in cryo-SEM, but this is likely because such structures would have to lie along the fracture plane of the vitrified solution with the proper orientation to be visualized. Sonication of HP-BNNT solutions prior to loading into capillaries can in some cases break up tactoid domains while retaining the Schlieren texture observed in Fig. 2b. Although the impurities in LP-BNNTs solutions inhibit BNNT dissolution and the formation of tactoids, capillary sonication results in the same long-range alignment as in HP-BNNT solutions, but with a significant quantity of undispersed particles present (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Polarized light microscopy (PLM) of BNNTs in chlorosulfonic acid (CSA) in flame-sealed 1 mm × 0.1 mm rectangular capillaries (a–c): unpolarized transmitted light and polarized light images with polarizer/analyzer at 0°/90° and 45°/135°, as depicted by the white crossed arrows. a Solution of lightly purified BNNTs (LP-BNNTs) at 7000 ppmw showing an isotropic solution with few birefringent domains. b Solution of highly purified BNNTs (HP-BNNTs) at 7260 ppmw showing 20 μm regions of strong birefringence. White arrows in b highlight the same elliptical structure in all three images. Red arrows highlight the same isotropic region in both polarized images. c Solution of HP-BNNTs at 7260 ppmw (the same solution as b) after ~5 s of bath sonication of the filled capillary. d High magnification PLM images after dilution of the solution in b to 3000 ppmw showing three different tactoids between crossed-polarizer and analyzer at various angles. The scale bar is 10 μm for all tactoid images. e Cryogenic scanning electron micrograph of BNNTs in CSA at 8000 ppmw showing aligned and isotropic regions in a biphasic BNNT solution.

The spontaneous alignment of BNNTs in liquid crystalline solutions is advantageous for the assembly of these building blocks into ordered macroscopic materials. Here, we are using lower concentration biphasic solutions in order to obtain processable volumes with the amount of HP-BNNT material available at this time. The lack of a fully liquid crystalline solution does not preclude the possibility of producing solid BNNT assemblies, because controlled flow induces alignment, even in an isotropic solution of rigid rods34—in fact, extensional flow was recently used to form continuous macroscopic fibers of BNNT/polyvinyl alcohol35 by adapting the spinning technique originally developed for making CNT/PVA fibers16. We produce aligned BNNT films of HP-BNNTs by manually shearing a small aliquot of their solution in CSA between two glass slides. The shear forces align nematic domains along the shear direction. Coagulation in acetone immediately after shearing preserves the ordered structure by quickly removing CSA from the BNNTs, which adhere to the glass slide. Fully coagulated films can be lifted from the glass slide and floated on the surface of a bath of water (Fig. 3a). The films can then be redeposited onto other structures, such as another glass slide (Fig. 3b). These thin BNNT films are highly transparent to visible light, uniform, and free of haze, as displayed by the sharp image of the Rice University shield below the film (Fig. 3c). PLM of these films (Fig. 3d) shows a dark field of view for crossed-polarizer orientations of 0°/90° and bright field of view for a 45°/135°, indicating BNNT alignment along the direction of shear (0°). The periodic birefringence intensity and absorbance can be fit to classical equation forms for anisotropic films, sin2(θ)cos2(θ) and sin2(θ), respectively36. Good fits (Fig. 3e) to the expected birefringence and absorbance indicate that the HP-BNNT film is aligned along the shear direction—although absorbance differences are minimal, because the visible light absorbance of BNNTs is low both for parallel and perpendicular orientations between the BNNT and the light polarization. The reduced birefringence intensities at 135° and 315° are likely due to a twist in the nematic director of the film36. The dichroic ratio, determined from the birefringence intensity in Fig. 3e, can be used37 to estimate the film order parameter Sbir = 0.56. Alignment of BNNT bundles can be observed by SEM, which shows mild alignment along the shear direction on the top layer of BNNTs (Fig. 3f).

a Photograph of a BNNT film made from a ~1 wt% solution of highly purified BNNTs (HP-BNNTs) floating on water with its original structure intact. b Photograph of the same film as in a redeposited onto a new glass slide and held at an angle to observe the film more easily. c Photograph of the BNNT film from b on the glass slide laid over the Rice shield, demonstrating high transparency. d Polarized light microscopy (PLM) images of the BNNT film on a glass slide: unpolarized transmitted light image and polarized light images with polarizer/analyzer at fixed at 0°/90°. The film was rotated to 45° for the last polarized light image and the double-sided white arrows in the lower left corners of the PLM images indicate the orientation of the shear axis for the film. e Plot of HP-BNNT film birefringence intensity normalized by incident light intensity (circles) and film absorbance (squares) against stage rotation angle. Birefringence intensity and absorbance are both plotted with model fits with coefficients of determination (r2) of 0.996 and 0.991, respectively. f Scanning electron micrograph of the BNNT film on glass. The double-sided white arrow indicates the shear axis for the film on SEM micrograph.

Liquid crystals are ideal precursors for aligned BNNT fibers. We produce fibers of neat HP-BNNTs via wet solution spinning, similar to other acid solution spinning processes38,39. The ~1 wt% HP-BNNT solution, or dope, is extruded vertically from a syringe through a 150 μm spinneret into acetone. Acetone coagulates the extruding filament into a solid fiber by extracting and reacting with CSA (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows SEM of typical fibers, with an average diameter of 27 μm ± 1 μm variation along the fiber length. Higher magnifications in SEM reveal a wrinkled skin with mild axial alignment of BNNTs along most of the fiber. The uneven surface morphology is likely a result of collapse induced by rapid evaporation of the coagulant from the BNNT filament after removal from the coagulant bath with no applied draw during extrusion. Closer inspection of the surface wrinkles shows BNNT alignment along their contours (Fig. 4c). Elsewhere are isolated domains of highly aligned BNNTs oriented along the fiber axis (Fig. 4d). Wide-angle X-ray scattering (Fig. 4e) of typical BNNT fibers shows axial alignment. The full-width-half-max (FWHM) of 42° indicates that the BNNT fiber has somewhat higher alignment than early CNT fibers40, which had a FWHM of ~60°. Polarized Raman spectra of that same BNNT fiber show a strong peak of BNNT at around 1370 cm−1 (Fig. 4f), which corresponds to the transverse optical A1 vibrational mode41,42. The intensity of the 1370 cm−1 band is shown to be polarization-dependent, which is consistent with BNNT alignment. Figure 4f shows that the maximum intensity of the characteristic peak at 1370 cm−1 is under the parallel polarization modes (V0° and V180°) and the minimum is under the perpendicular polarization (V90°) mode, suggesting a two-fold symmetry. The peak intensity ratio of V0°:V90° is estimated as 2.4:1, consistent with mild BNNT alignment along the fiber axis. This ratio is somewhat lower than the Raman peak ratio of 5.1:1 observed in early CNT fiber40. The strongest BNNT fibers show an average (over twelve measurements) tensile strength of 15.7 MPa ± 1.6 MPa and Young’s modulus of 1.46 GPa ± 0.18 GPa, based on a diameter of 27 μm and circular cross-section. The BNNT fiber properties reported here are encouraging, given the similarities between BNNTs4 and CNTs43. In fact, these initial results are comparable to those of early solution-spun HiPco CNT fiber, which had a strength of ~1 to 5 MPa and modulus of ~0.1 to 1 GPa (see Chapter 3 of ref. 44). The performance of early HiPco CNT fiber was limited by material impurity, but was later improved by two orders of magnitude by optimizing HiPco material processing38. Later, CNT fiber performance was further improved by a factor of ~50 by combined advances in CNT quality and spinning18.

a Photograph of typical segment of fiber made from highly purified BNNTs taped to a benchtop under tension. b Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showing a 27 μm diameter fiber with wrinkled and smooth areas of the fiber skin. c SEM showing mild alignment of BNNTs along the wrinkle contours. d SEM of a smooth area of the fiber surface showing strong BNNT alignment along the fiber axis. e Wide-angle X-ray scattering of BNNT fiber (black dots) plotted against azimuthal angle shows two peaks from the fiber fit with a Gaussian curve (blue line) with full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of 42°. f Raman spectra of BNNT fiber with V0°, V30°, V60°, V90°, V120°, V150°, and V180° polarizer/analyzer modes. Laser excitation was given by a 785 nm laser. A sharp peak at ∼1370 cm−1 is characteristic of BNNTs.

In conclusion, we have shown that purified few-walled BNNTs are soluble in CSA and can be processed into macroscopic materials. BNNTs form nematic liquid crystals in CSA, including tactoids in biphasic solutions at the concentrations we tested (~1 wt%). We measured the aspect ratio of BNNTs in bulk using capillary thinning rheometry, which provides an important structural parameter (similar to intrinsic viscosity in polymers), because the mechanical and thermal properties of macroscopic BNNT materials should scale with aspect ratio, as shown for CNTs18. We expect BNNTs to form fully liquid crystalline solutions, and the concentration of this transition is expected to decrease with higher aspect ratio45 and higher purity. Thus, the challenge of forming fully liquid crystalline BNNT solutions at processable concentrations lies in increasing both of these material parameters. We process BNNT liquid crystals into aligned films and neat BNNT fibers with encouraging structural order. Currently, the properties of these BNNT films and fibers are likely limited by a combination of aspect ratio, solution quality, and processing parameters. Further improvements in material synthesis, purification, and mapping of the liquid crystalline phase diagram will yield optimal processing dopes. The nematic transition for solutions of CNTs has been observed through rheological characterization of CNT-superacid solutions46, and such experiments could help identify this transition for BNNT solutions. Fully liquid crystalline, higher concentration dopes will be explored in future experiments as HP-BNNTs become more broadly available. Such improved dopes will allow spinning in a broader parameter space with stable filament draw, uniform diameter, higher BNNT alignment, and higher packing density, all of which are directly correlated with macroscopic fiber properties18. This work demonstrates a scalable methodology for producing ordered BNNT materials that retain their extraordinary properties in extreme environments.

Methods

Synthesis and purification of BNNTs

BNNTs for this research were synthesized by BNNT LLC (Newport News, VA), using the HTP method24. The as-synthesized samples (product code SP10) were then purified to remove elemental boron47, yielding LP-BNNTs (product code SP10R). LP-BNNTs include non-nanotube boron nitride species, which can be removed by high-temperature steam purification27. LP-BNNTs were further purified by a high-temperature steam purification process to remove non-nanotube BN species, yielding HP-BNNTs (product code SP10RX). TGA was performed using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 3+ in air with a 10-min hold at 110 °C and a temperature ramp of 10 °C/min to 1100 °C for all samples.

Solution preparation and spectroscopy

The BNNTs were dissolved in CSA at a concentration of ~1% by weight. Pure (99.9%) CSA was used as received from Sigma-Aldrich. The vial containing BNNTs and CSA was first vigorously shaken by hand to break apart the BNNT “puff ball,” prior to mixing for 40 min with a FlackTek DAC 600 SpeedMixer forming a viscous solution. UV–vis spectra of the BNNTs dissolved in CSA and dispersed in 1% by weight aqueous sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were collected using a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer. Quartz cuvettes with PTFE caps and path lengths of 1 mm and 1 cm were used for CSA and SDS samples, respectively. BNNT solutions in CSA were quenched and rinsed with deionized water until a neutral pH was reached. The BNNTs were then dried to collect FTIR spectra. A Nicolet iS50 instrument was used with a diamond ATR accessory, averaging 32 scans at 4 cm−1 resolution.

Rheology and aspect ratio determination of BNNTs

Viscosity-averaged aspect ratios were estimated using a custom-built capillary thinning rheometer, described by ref. 29. The extensional viscosity is determined by the rate-of-change of the filament diameter. Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the final frames of filament thinning that were recorded during the experiment. An extensional viscosity of 0.4 Pa s was determined for the 7260 ppmw solution. A density of 1.50 g/cm3 was used for the HP-BNNTs to calculate the viscosity-averaged aspect ratio. This density was calculated assuming that a single-walled BNNT has the same areal density as a single sheet of h-BN (1318 m2/g), following along with similar calculations for graphene48. The density of HP-BNNTs was calculated using the average number of walls (3.5) and outer diameter (5.8 nm ± 0.3 nm), while also assuming with a BN bond length of 1.446 Å, and an interlayer spacing of 3.331 Å (refs. 28,49).

BNNT films and fibers

Shear-aligned films were produced according to the method described by ref. 50, using acetone as the coagulant. Just prior to shearing the solution, a powered 20 kHz Qsonica Q55 tip sonicator was lightly brushed along the outer surface of the top glass, scratching the glass and merging tactoid domains. The top slide was then rapidly sheared across the bottom slide and immediately plunged into an acetone coagulant bath. Shear-aligned films were annealed in air at 400 °C for 20 min to improve electron imaging quality by removing residual acid and organic molecules from coagulation. BNNT fibers were produced by extruding BNNT solution through a 150 μm spinneret into a coagulation bath of acetone, based on methods described by ref. 18. Fiber was extracted from the bath and allowed to dry under ambient conditions overnight, before tensile testing on an ARES-G2 rheometer, using 4 mm fiber segments.

Light microscopy

Portions of HP-BNNT and LP-BNNT CSA solutions were loaded and flame-sealed into glass capillaries with an inner width of 100 μm, which were then flame-sealed. Some sealed capillaries were sonicated by submerging them into a Branson 1800 bath sonicator at 40 kHz for ~5 s. Light microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam 208 camera. The contrast for images of sealed capillaries was adjusted in MatLab and ImageJ. Each set of PLM images received the same contrast adjustments. Images of the BNNT film that were used to study birefringence and absorption were taken with the camera operating in black-and-white mode without contrast adjustments. Intensities for each rotation angle were determined by averaging the pixel values across the entire field of view (~1 mm × 0.65 mm). The incident light intensity was determined by capturing an image with no sample and only the polarizer inserted. All images for this analysis were taken using the same microscope illumination settings and intensity values were normalized by camera exposure time.

Atomic force microscopy

Samples for atomic force microscopy (AFM) were prepared from solutions diluted to ~1 ppmw and drop-casted onto a freshly cleaved mica surface, preheated to 400 °C using a hot plate. Diethyl ether was used to remove residual acid from the mica before drying the sample with room temperature air flow, followed by oven treatment at 100 °C for an hour. The AFM measurements were performed with a Nanoscope IIIa scanning probe microscope controller from Digital Instruments operated in the tapping mode. Micrographs were processed in the Gwyddion software package, and the height profiles and length of 100 randomly selected individual nanotubes were collected.

Electron microscopy

SEM of dry material was performed using an FEI Helios NanoLab 660 SEM/FIB. Shear-aligned films were imaged directly on glass, and the as-produced material was imaged on carbon tape. SEM samples received no conductive layer prior to imaging. An accelerating voltage of ~1 kV and working distance of ~3.5 mm was used for SEM characterization.

TEM and Cryo-TEM of BNNT-CSA solutions were performed by a Thermo Fisher (formerly FEI) Talos 200C high-resolution TEM at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Cryo-specimens were maintained below −175 °C in the microscope using a Gatan 626 cryo-holder, and imaged in the low-dose-imaging mode to reduce electron-beam radiation damage. Images were recorded digitally by an FEI Falcon III direct-imaging camera and the TIA software, with the help of the “Volta phase-plate” (FEI) to enhance image contrast.

Cryo-SEM of BNNT-CSA solutions was performed by a Zeiss Ultra Plus HR-SEM equipped with a Leica VT100 cold-stage system. Specimens were maintained at −145 °C, and imaged without coating at a low acceleration voltage of 0.6 kV to achieve a state of charge balance, avoiding specimen charging and imaging artifacts51. Micrographs were taken at short working distance (3.3–3.8 mm) with an in-the-column secondary electron detector. Cryo-TEM and cryo-SEM specimens were prepared in a controlled environment vitrification system52, continuously purged with dry N2 to prevent superacid reaction with moisture. For cryo-TEM specimens, a drop was applied onto a perforated carbon film supported on a 3 mm copper TEM grid. The drop was blotted with a fiberglass filter-paper to form a thin film (<300 nm) and vitrified by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Cryo-SEM specimens were prepared by dipping a 3 mm grid in the solution and placing it between two gold planchettes. The specimen was plunged into liquid nitrogen with dedicated tweezers53, and freeze-fractured in a BAF060 unit (Leica AG, Liechtenstein) at −167 °C.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were obtained with a DXR2 Raman microscope system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a laser excitation of 785 nm under ×50 objective. The BNNT fiber samples were placed onto a glass slide, and analyzed within the Raman shift range of 200–3400 cm−1. The Raman microscope was operated with the following experimental parameters: excitation laser wavelength (785 nm), laser intensity (30 mW), and aperture type (50 µm pinhole aperture). The spectral background was corrected using smart subtraction offered by the DXR2 Raman microscope to remove interference caused by fluorescence. The alignment of the BNNT fiber was determined by recording a Raman spectrum every 30° from 0° to 180° between the incident polarization and the fiber axis. While the polarizer was set vertically, Raman spectra were collected from BNNT fiber in the order of V0° (parallel polarization), V30°, V60°, V90° (perpendicular polarization), V120°, V150°, and V180° polarizer/analyzer modes.

Wide-angle X-ray scattering

Wide-angle X-ray diffraction was performed using a small/wide-angle diffractometer (Molecular Metrology SAXS system), equipped with a sealed microfocus tube (MicroMax-002 + S) emitting Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å), two Göbel mirrors, and three pinhole slits. The generator is powered at 45 kV and 0.8 mA. The scattering patterns were recorded by a 15 × 15 cm two-dimensional imaging plate (BAS-IP-MS, FUJIFILM), positioned about 6 cm behind the sample. Exposition time was about 18 h. The single fiber sample was fixed on a two-dimensional holder perpendicular to the beam, and measured under vacuum at ambient temperature. The imaging plate was scanned by a Fluorescent Image Analyzing System (FLA-7000), and analyzed by FLA-7000 ImageReader software with 100 μm resolution.

Data availability

The main data that support the findings of this study are available in the article and Supplementary Information. Raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chopra, N. G. et al. Boron nitride nanotubes. Science 269, 966–967 (1995).

Blase, X., Rubio, A., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Stability and band gap constancy of boron nitride nanotubes. EPL 28, 335–340 (1994).

Chopra, N. G. & Zettl, A. Measurement of the elastic modulus of a multi-wall boron nitride nanotube. Solid State Commun. 105, 297–300 (1998).

Wei, X., Wang, M.-S., Bando, Y. & Golberg, D. Tensile tests on individual multi-walled boron nitride nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 22, 4895–4899 (2010).

Chang, C. W. et al. Isotope effect on the thermal conductivity of boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 1–4 (2006).

Thibeault, S. A. et al. Nanomaterials for radiation shielding. MRS Bull. 40, 836–841 (2015).

Kang, J. H. et al. Multifunctional electroactive nanocomposites based on piezoelectric boron nitride nanotubes. ACS Nano 9, 11942–11950 (2015).

Nautiyal, P. et al. Oxidative unzipping and transformation of high aspect ratio boron nitride nanotubes into “White Graphene Oxide” platelets. Sci. Rep. 6, 29498 (2016).

Chen, X., Dmuchowski, C. M., Park, C., Fay, C. C. & Ke, C. Quantitative characterization of structural and mechanical properties of boron nitride nanotubes in high temperature environments. Sci. Rep. 7, 11388 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Mechanical strength of boron nitride nanotube-polymer interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 253105 (2015).

Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354, 56–58 (1991).

Harris, C. E., Shuart, M. J. & Gray, H. R. A survey of emerging materials for revolutionary aerospace vehicle structures and propulsion systems. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Langley Research Center. (2002).

Taylor, L. W. et al. Improved properties, increased production, and the path to broad adoption of carbon nanotube fibers. Carbon 171, 689–694 (2021).

Li, Y.-L., Kinloch, I. A. & Windle, A. H. Direct spinning of carbon nanotube fibers from chemical vapor deposition synthesis. Science 304, 276–278 (2004).

MIRALON Yarn Technical Data Sheet. Huntsman Corporation. https://huntsman-pimcore.equisolve-dev.com/Documents/Miralon%20Yarn%20_US_e.pdf (2020).

Vigolo, B. et al. Macroscopic fibers and ribbons of oriented carbon nanotubes. Science 290, 1331–1334 (2000).

Behabtu, N. et al. Strong, light, multifunctional fibers of carbon nanotubes with ultrahigh conductivity. Science 339, 182–186 (2013).

Tsentalovich, D. E. et al. Influence of carbon nanotube characteristics on macroscopic fiber properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 36189–36198 (2017).

Zhang, M., Atkinson, K. R. & Baughman, R. H. Multifunctional carbon nanotube yarns by downsizing an ancient technology. Science 306, 1358–1361 (2004).

Chen, G., Futaba, D. N., Sakurai, S., Yumura, M. & Hata, K. Interplay of wall number and diameter on the electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube thin films. Carbon 67, 318–325 (2014).

Kleinerman, O. et al. Dissolution and characterization of boron nitride nanotubes in superacid. Langmuir 33, 14340–14346 (2017).

Ramesh, S. et al. Dissolution of pristine single walled carbon nanotubes in superacids by direct protonation. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 8794–8798 (2004).

Green, M. J., Parra-Vasquez, A. N. G., Behabtu, N. & Pasquali, M. Modeling the phase behavior of polydisperse rigid rods with attractive interactions with applications to single-walled carbon nanotubes in superacids. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 084901 (2009).

Smith, M. W. et al. Very long single- and few-walled boron nitride nanotubes via the pressurized vapor/condenser method. Nanotechnology 20, 505604 (2009).

Zhi, C. et al. DNA-mediated assembly of boron nitride nanotubes. Chem. Asian J. 2, 1581–1585 (2007).

Kode, V. R. et al. Purification and assembly of DNA-stabilized boron nitride nanotubes into aligned films. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 2099–2105 (2019).

Marincel, D. M. et al. Scalable purification of boron nitride nanotubes via wet thermal etching. Chem. Mater. 31, 1520–1527 (2019).

Pauling, L. The structure and properties of graphite and boron nitride. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 56, 1646–1652 (1966).

Tsentalovich, D. E. et al. Relationship of extensional viscosity and liquid crystalline transition to length distribution in carbon nanotube solutions. Macromolecules 49, 681–689 (2016).

Donald, A., Windle, A. H. & Hanna, S. Liquid Crystalline Polymers (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Jamali, V. et al. Experimental realization of crossover in shape and director field of nematic tactoids. Phys. Rev. E 91, 042507 (2015).

Modlińska, A., Alsayed, A. M. & Gibaud, T. Condensation and dissolution of nematic droplets in dispersions of colloidal rods with thermo–sensitive depletants. Sci. Rep. 5, 18432 (2015).

Davis, V. A. et al. True solutions of single-walled carbon nanotubes for assembly into macroscopic materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 830–834 (2009).

Batchelor, G. K. The stress generated in a non-dilute suspension of elongated particles by pure straining motion. J. Fluid Mech. 46, 813–829 (1971).

Khoury, J. F., Vitale, J. C., Larson, T. L. & Ao, G. Boron nitride nanotubes enhance mechanical properties of fibers from nanotube/polyvinyl alcohol dispersions. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 77–86 (2021).

Zamora-Ledezma, C. et al. Anisotropic thin films of single-wall carbon nanotubes from aligned lyotropic nematic suspensions. Nano Lett. 8, 4103–4107 (2008).

Chowdhury, R. A., Peng, S. X. & Youngblood, J. Improved order parameter (alignment) determination in cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) films by a simple optical birefringence method. Cellulose 24, 1957–1970 (2017).

Ericson, L. M. Macroscopic, neat, single-walled carbon nanotube fibers. Science 305, 1447–1450 (2004).

Blades, H. Dry jet wet spinning process. United States Patent 3767756A. Filed June 30, 1972.

Zhou, W. et al. Single wall carbon nanotube fibers extruded from super-acid suspensions: Preferred orientation, electrical, and thermal transport. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 649–655 (2004).

Arenal, R. et al. Raman spectroscopy of single-wall boron nitride nanotubes. Nano Lett. 6, 1812–1816 (2006).

Chang, H. et al. Determining the orientation and interfacial stress transfer of boron nitride nanotube composite fibers for reinforced polymeric materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 6670–6676 (2019).

Yu, M. Strength and breaking mechanism of multiwalled carbon nanotubes under tensile load. Science 287, 637–640 (2000).

Ericson, L. M. Macroscopic Neat Single-wall Carbon Nanotube Fibers (Rice University, 2004).

Onsager, L. The Effects of Shape on the Interaction of Colloidal Particles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 51, 627–659 (1949).

Davis, V. A. et al. Phase Behavior and Rheology of SWNTs in Superacids. Macromolecules 37, 154–160 (2004).

Chen, H., Chen, Y., Yu, J. & Williams, J. S. Purification of boron nitride nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 425, 315–319 (2006).

Peigney, A., Laurent, C., Flahaut, E., Bacsa, R. & Rousset, A. Specific surface area of carbon nanotubes and bundles of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 39, 507–514 (2001).

Laurent, C., Flahaut, E. & Peigney, A. The weight and density of carbon nanotubes versus the number of walls and diameter. Carbon 48, 2994–2996 (2010).

Headrick, R. J. et al. Structure–property relations in carbon nanotube fibers by downscaling solution processing. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–8 (2018).

Liberman, L., Kleinerman, O., Davidovich, I. & Talmon, Y. Micrograph contrast in low-voltage SEM and cryo-SEM. Ultramicroscopy 218, 113085 (2020).

Bellare, J. R., Davis, H. T., Scriven, L. E. & Talmon, Y. Controlled environment vitrification system: an improved sample preparation technique. J. Electron Microsc. Tech. 111, 87–111 (1988).

Issman, L. & Talmon, Y. Cryo-SEM specimen preparation under controlled temperature and concentration conditions. J. Microsc. 246, 60–69 (2012).

Acknowledgements

BNNTs were provided by BNNT LLC. Cryo-TEM and HR-SEM imaging was performed at the Laboratory for Electron Microscopy of Soft Matter, supported by the Technion Russell Berrie Nanotechnology Institute (RBNI). We acknowledge the use of the Electron Microscopy Center (EMC) at Rice University. Wide-angle X-ray scattering was performed by Dr. Rafail Khalfin. Funding was provided by AFOSR grant FA9550-18-1-0014, Welch Foundation grant C-1668, by CONACyT (Mexico, No. 710115) to C.M.J., and by a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship (NSTRF14) to R.J.H., Grant No. NNX14AL71H. Additional funding was provided by NSF grant 1807737 and 2108838 and by the Department of Energy (DOE) award DE-AR0001015 (Advanced Research Projects Agency, Energy). The Rice-Technion collaboration was supported by AFOSR grant FA9550-19-1-7045 and a United States−Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) grant 2016161. The development of SP10RX by BNNT Materials LLC was supported by ONR PHII SBIR N68335-19-C-0560.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J.S.G., C.M.J., A.M.Y., O.S.D., A.D.S.M., D.V.K., D.M.M., Y.T., A.A.M., and M.P. conceived and designed solution preparation and characterization experiments. A.M.Y. and Y.T. conceived and designed cryogenic electron microscopy experiments. M.P., A.A.M., and Y.T. supervised the respective members of the study. C.J.S.G. performed solution preparation, PLM, UV–vis spectroscopy, room temperature SEM, extensional rheology, and fiber tensile testing. C.M.J. performed AFM and FTIR. A.M.Y. performed cryo-SEM, cryo-TEM, room temperature TEM, and WAXS. C.J.S.G. and O.S.D. conducted fiber spinning experiments. C.J.S.G. prepared films with guidance from R.J.H. L.R.S. and M.W.S. synthesized and purified the material. C.P. and S.H.C. conducted polarized Raman. C.J.S.G. wrote the manuscript with guidance from A.A.M. and M.P. All authors discussed results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.W.S. is the Chief Scientist and L.R.S. is the Product Development Manager at BNNT Materials, LLC, which has commercialized the synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yongho Joo and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simonsen Ginestra, C.J., Martínez-Jiménez, C., Matatyaho Ya’akobi, A. et al. Liquid crystals of neat boron nitride nanotubes and their assembly into ordered macroscopic materials. Nat Commun 13, 3136 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30378-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30378-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.